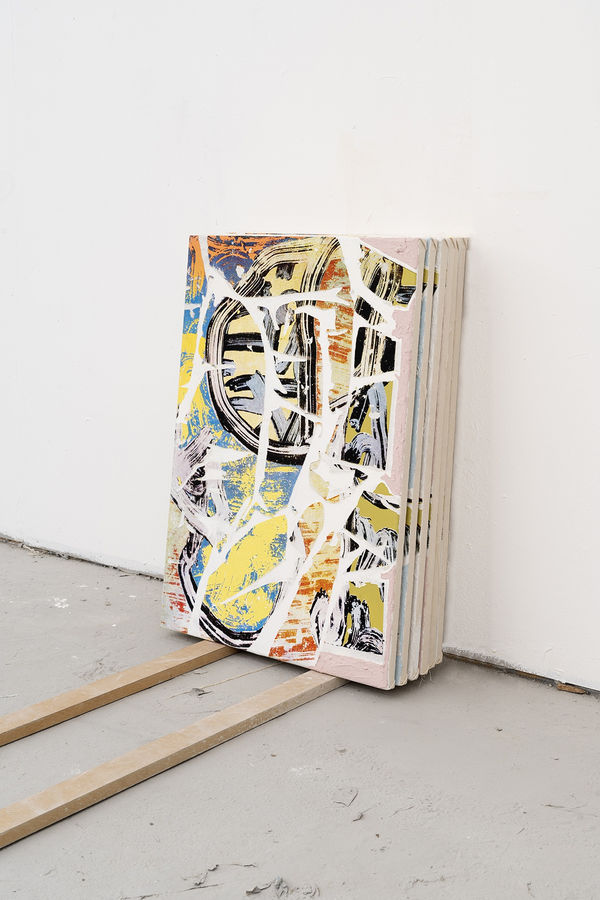

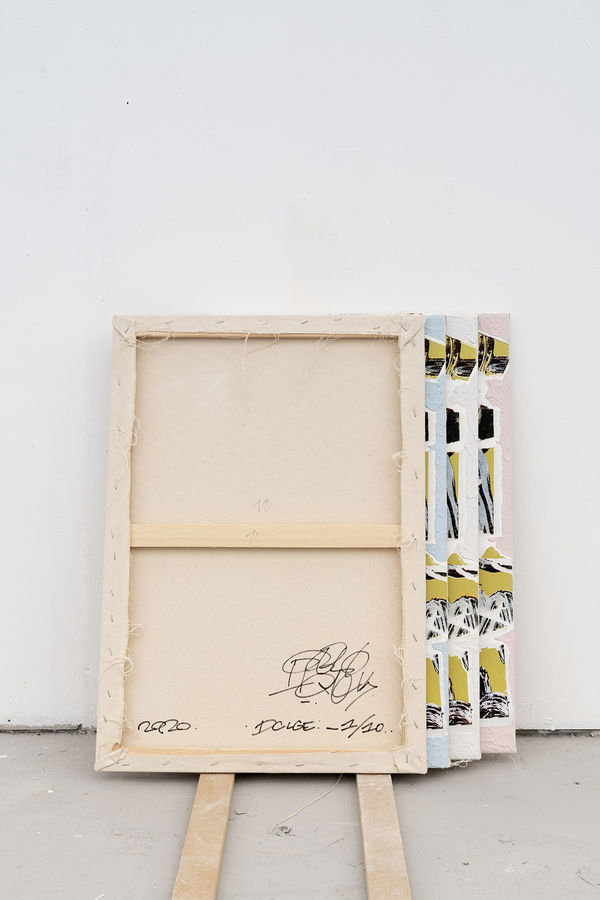

PABLO TOMEK: DÉCOLLAGE, 2020

Past viewing_room

Painter-sculptor, painter-photographer, Pablo Tomek is also a painter-painter. This is what he reminds us of by continuing his series of canvases carried out using sponges, taking both their subjects and their techniques from workmen, from whitewash spread on worksite windows, to power washers erasing graffiti in public spaces. Presented “shoulder to shoulder like a frieze” Tomek restates his attachment for these rough writings. Much like amateur and anonymous signs of the street, of which Brassaï said: “Carve one’s name, one’s love, a date, on the wall of a building, this ‘vandalism’ cannot be explained by the simple need to destroy. I see there more the instinct to survive of all of those who cannot erect pyramids and cathedrals to leave their name for posterity.”

Tomek specifies: « Different from my first canvases, these designs and messages are no longer excuses for abstraction, but are reproduced purely and dictate the composition of the work. These signs I use as intrusions in the composition of the pieces have become the subject itself of the painting.” We find here the idea of the printer: Tomek continues his attempt to make a photograph by painting, and a painting using photography. The painter’s technique becomes then quasi-photographic, a post-production scan of the effects, of filters well-established by the artist.

Pablo Tomek has always rejected the label of Street Art to define his work. Widely known today thanks to social networking, the mainstream press, the auction houses, the movement evokes in the collective imagination a sort of bad pop art, kitsch and unoffensive. Pablo Tomek comes from the world of graffiti, an approach that is encoded, sneaky, risky, clandestine. A world where he gained experience by breaking the rules. But the definition of Street Art by Pierre Restany when describing Karel Appel could cause trouble: “(Karel Appel) assimilates ‘street art,’ ‘Throw away Art,’ the art of the street, of rubbish, of objects we throw away, to a metaphoric game, to recreation in recreating. He is modest, because he knows that this game is the very essence of the world: this industrial discarded object, that he ‘treats’ after having taken it just at the moment of collapse of its function state, he takes it from the nothing of obsolescence and raises it to a dimension of completely new, poetic, and human expressivity. He humanizes and poetizes the standard product of the machine, the object that is worn out, used-up, thrown away, lost: it’s the return of the prodigal son.”

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.